NewsHour: John Knoop Remembered on PBS NewsHour

John Knoop died in his sleep on January 12th, 2017. John was a remarkable and creative person on so many levels and his serene and beautiful spirit is missed by the many people whose life he touched.

Contacts:

Primary (daughter): Tanya Knoop belovedjohnknoop@gmail.com,

Colleagues/friends: George Csicsery geocsi@zalafilms.com, Toby McLeod tm@sacredland.org, Will Parrinello willmvfg@gmail.com, Gaetano Maida gkmaida@comcast.net, Andy Black ablacknow@aol.com, Karina Epperlein karina@karinafilms.us

----------------------

Remembrance from friends and family

Tanny Hodges

Elizabeth Farnsworth

Karina Epperlein

Rudy Wurlitzer

--------------------------

John Knoop, Local Filmmaker, Cofounder of Film Arts Foundation

By Gaetano Kazuo Maida, with much appreciation from the family

Bay Area cinematographer, producer, and cofounder of the seminal indie filmmaker organization Film Arts Foundation, John Knoop, died in his sleep on January 12th at his home in El Cerrito. He was 77.

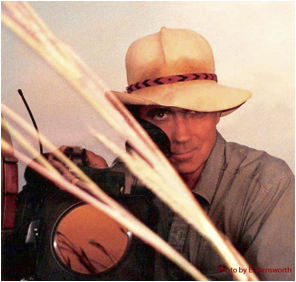

John on Location. 1994. E. Farnsworth

“He used the same talents in preparing NewsHour reports as he did in making feature-length films. He got just the right shot at just the right time of day. He treated interviewees with respect and they told him things they wouldn’t tell anyone else. He had a calmness, which people sensed. He was deeply intelligent and empathetic.” – Elizabeth Farnsworth, former chief correspondent, The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer.

Knoop and Farnsworth on Location. 1994. Jamie Kibben

Between 1990 and 1995, together with Elizabeth Farnsworth and soundman Jamie Kibben, John coproduced and filmed over thirty documentary reports for the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour in countries ranging from Vietnam and Cambodia to Haiti, Guatemala and Peru. In 1993, in Cambodia, John accompanied UN troops in conflicted areas partially controlled by the Khmer Rouge to film the soldiers’ preparations for UN-sponsored constituent assembly elections. In 1994 he, Kibben and Farnsworth were deported from Haiti after having been placed under house-arrest and losing their passports and reporting credentials. They had offended the ruling military junta, which had violently overthrown President Jean Bertrand Aristide.

“John was courageous in conflicted places, kind and reassuring to interviewees, and brilliant in framing shots and the stories we wanted to tell. I feel lucky to have worked with him and Jaime Kibben on the PBS film Thanh’s War and on the NewsHour pieces,” Elizabeth Farnsworth said.

As producer/director, Knoop’s documentaries include River Out of Time, Memories of the Hunt, Café Nica, Report from Iraq, Sea of Cortez, and Awakening From Sorrow. He was cinematographer on many noted films, including In the Light of Reverence, by Christopher McLeod and Malinda Maynor; Louie Bluie, by Terry Zwigoff; Peace Is Every Step, by Gaetano Kazuo Maida; N Is A Number and Where the Heart Roams, by George Csicsery; Maria’s Story, by Pamela Cohen and Manona Wall; Cowgirls, by Nancy Kelly; Shadow Master, by Larry Reed; and Voices from Inside, by Karina Epperlein. His last completed project, co-directed with Epperlein, was Awakening from Sorrow: Buenos Aires 1997 (2009).

In his 2013 memoir, Fault Lines—A Nomadic Filmmaker’s Journal, he wrote, “Being part of an attempt to report the truth was always a satisfying challenge.”

With Siblings and Goat. Circa1956. Fred Knoop

Knoop grew up on a farm in Ohio, about twenty miles east of Cincinnati, in a family of four brothers and a sister. His father was editor of Minicam, a photography magazine which later became Modern Photography. His mother was a school teacher, goat farmer, and granddaughter of Rudolph Wurlitzer, famed for his company’s Mighty Wurlitzer movie palace organs and Art Deco juke boxes.

John's Piper Airplane. 1956. Fred Knoop

As a teenager, John learned to fly small planes, and bought his first, a Piper Vagabond, when he was only sixteen. He wrote, "I soon thought of its wings as an extension of my arms..." He made his way to Columbia University where he "was a glutton for the cultural benefits I came to New York City to feed on," as he later wrote, but he dropped out after a year to travel by motorcycle with a college roommate across the U.S. and then through Central and South America. After that adventure he made his way home and married Judith Mayersohn, his high school sweetheart. The couple soon left for Europe, ending up in Majorca, Spain, where their daughters Tanya and Michelle were born. They met and were befriended by author Robert Graves there, and found themselves part of a community of Bohemian exiles of all types. With some encouragement from Graves, Knoop wrote short stories and a novella, although immediate publishing success eluded him.

On the Way to Argentina. 1958. Fred Knoop

After 3 years the couple returned to the U.S. where Knoop found a job in Ohio working for a magazine, The Farm Quarterly. The job grew from a research position to writing articles, doing photography, editing a book, heading up the magazine’s new West Coast office in San Francisco, and ultimately to producing a documentary on modern farming, Farm in 1967. This marked a turning point in his work. He called it a “learning experience in experimental filmmaking, masquerading as an industrial documentary.” It opens with an accelerated telephoto sunrise, followed by a rapid-fire montage composed from the strongest images in the film, cut to Stravinsky's Rite of Spring. It is un-narrated and purely expository, a lyrical portrait of modern agriculture, with no sales message.” It was a revolutionary film and captured the zeitgeist of the psychedelic age.

In the 1960's, he settled in San Francisco and was drawn into the city's iconic circles of artist, musicians, and activists. Soon after the birth of his third child and only son Geoffrey, John moved to a loft on Natoma St. with Sharon Hennessey. His life was now devoted to film—learning about it, making experimental shorts, filming for other producer/directors, and later switching to the world of documentary filmmaking. His loft on Natoma Street in the city soon housed an editing room and a photographic darkroom. By 1975 he and a few other filmmakers pooled their resources to purchase a professional flatbed editing machine, and form the nonprofit Film Arts Foundation (FAF), the first of its kind to serve the independent filmmaking community. (FAF programs were later incorporated into San Francisco Film Society.)

While recovering from injuries sustained in a climbing accident, Knoop began to dedicate himself to bicycle riding to strengthen his body. Oakland filmmaker and friend George Csicsery remembers, “(His) bicycling was legendary. For years he commuted from his home in San Anselmo, where he lived with his wife Sharon and daughters Hennessey and Savannah, to the studio on Natoma Street by bicycle. John and I once traveled to Europe together for a month of filming. He was responsible for packing all the gear we would need, and he had promised to compact everything into a few boxes. When we got to the airport I noticed that one of the boxes was larger than I had expected, and asked John what it was. He said it was just some extra gear we needed. It was only after arriving in Germany and packing everything into a station wagon that he revealed the contents of the box: his bicycle.”

He was known for his attraction to danger: flying planes, riding motorcycles, climbing, whitewater rafting, epic bike rides, and filming in war zones. Filmmaker Gaetano Maida recalls, “We were in Bangkok, Thailand, filming a story about a remarkable woman, a social activist, and we were getting footage of her making a speech in a public park filled with thousands of people, families—children and grandparents and students—peacefully rallying to protest the new military regime. They decide to march to the government buildings not far away and we followed, filming our subject and the crowd as they walked. Suddenly we hear gunfire a bit in front of us, rapid machine gun fire, and everyone around us panics and starts to run. John picks up his camera and immediately heads toward the sounds. I run and grab him and remind him we no longer have our driver, no batteries, no tape, no escape, no way to film, and he reluctantly agrees to retreat with us back to our hotel. But his first instinct was to go to the drama no matter how dangerous.”

Knoop wrote while in El Salvador during the civil war, filming what became Maria’s Story, “…as we are bedding down, there’s the eerie whirr of an incoming 120mm artillery shell that lands just beyond our camp. I feel the shock wave of detonation and grab my camera… A compa grabs my hand and tows me toward a huge protective boulder, saying, ‘You’ve got to be lying flat because it’s the shrapnel that’s dangerous.’ I lay behind the boulder, recording nervous conversations while nine more rounds fall along the ridge above us. It occurs to me that I’ve been so intent on recording the event that I’ve scarcely registered fear.”

He was riding his bike at night in San Francisco in on January 27th, 1997 when he crashed in Golden Gate Park. He was temporarily paralyzed from the neck down and spent a month in the hospital. He told a daughter, “It’s only life. My number was up. You’ll never know how much I got away with, how lucky I’ve been.” Days after being released from the hospital, having been told by his doctors that he may never walk again and against their orders, John got on a plane with Andy Black to meet Susana Blaustein Munoz in Argentina to shoot Munoz’s documentary, Awakening from Sorrow: Buenos Aires 1997. Munoz said, "John was an amazing friend. We escaped the Gulf war together during the making of My Home, My Prison, and he generously loaned his editing table that he brought on his back up a steep flight of stairs. I believe he really cared deeply about people and politics. He was a resilient man beyond belief. He taught me courage."

The trip’s physical demands took its toll on Knoop, who realized he could no longer do the kind of rigorous physical work required of a cinema verite director of photography. The realization that he still had his mobility, albeit limited, dramatically changing the direction of his life led him to tell friends, “I have the best bad luck of anyone I know.”

From here on, John dedicated himself to his recovery, healing his injured spinal cord, learning how to walk again. Embracing his new life in a “wrecked body” as he called it, with curiosity, courage, and dignity inspired people all around him. He made two more films with his friend and colleague Karina Epperlein, attended film festivals, enjoyed extensive travels to wild hot springs in his favorite corners of Nevada, taking in the healing waters at Ojo Caliente, living a frugal simple life.

John also took time to consult younger filmmakers, generously sharing his knowledge and wisdom. Having always loved the process of editing, he completed several short videos from old footage. Friends would drop by and chat over mescal late into the night. But the major focus in his last years was his memoir Fault Lines – A Nomadic Filmmaker’s Journal, which not only describes his adventures and work, but also highlights his philosophical outlook and poetic voice. Over many years, he kept rewriting and revising, always aware that it is all but a dream.

He is survived by his children, Tanya, Michelle, Geoffrey, Hennessey, and Savannah, and siblings Janet Kurtz, Christopher Knoop, Anthony Knoop, and Rudolph Knoop.

-------------

Chronical article: John Knoop, filmmaker and daredevil, dies